Next I went to see the retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), which was truly comprehensive at almost 150 works, and incredibly impressive. Without doubt, Turner forms a talented link between early Romanticism and Impressionism, but I'll have to admit I was not as crazy about his later, impressionistic works. Nonetheless, there were some amazing things to see.

There was way too much visual information (I'd heard the show described as "exhausting"), so I didn't and won't concentrate as much on his watercolors and gouaches. He had a real feel for them, though, and they really are some of the best watercolors I'd seen. There's also a good number of sketches and studies that are interesting to get an impression of his process, but there's no reason to discuss those here.

The show is arranged chronologically, more or less, but the cool thing is that--since Turner switched focus somewhat markedly a few times during his career--it ends up being thematic, at the same time.

--Conway Castle (1800, pencil, watercolor, and gum Arabic on paper)

I will actually start with a watercolor, though. This was where I started to get a feel for how so much of his work concerns this idea of the connection between built structures and their surrounding environment, and the personalities, the people who inhabit both. He hadn't begun animating his scenes with people here yet, but he was obviously quite friendly with the aristocracy, because he painted a ton of the castles throughout the U.K.

Anyway, you may need to click this, and hopefully you can see it, but you have to follow those sharp horizontal lines formed by the choppy sea from right to left. When your eye gets to shore, all those lines encounter curves, curves in the rock formation, and another on the hill with the small tree growing out of it. They all lead your eye right back to the castle. The darker clouds in the sky above that do the same thing. It really makes the castle the star of this show, and forms a loving relationship between the building and the land it oversees.

--The Pass of Saint Gotthard (1804, oil on canvas)

The other thing he was interested in around this time is the confrontation between human achievements and the powerful forces of Nature. There's another painting of Saint Gotthard, The Devil's Bridge, which much like this one, shows both our wondrous abilities to surmount daunting natural obstacles, but the delicate, almost spooky precariousness of it, as well. The stone pathway shown here I'm sure is relatively safe, but I can't imagine what it must have taken to construct it, and it still appears like a route that would require some measure of courage. It's at once beautiful and eery. He's put figures in the foreground, too, it's an interesting place for them, since in these wide expanses, individuals could so easily get swallowed up; he allows them to be prominent. What's interesting here, though--and I didn't say "people"--the figures are actually pack animals, their guides presumably behind them, out of frame. How many of them are there? Who are they? Merchants? Nomads? We'll never know.

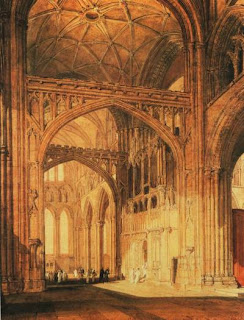

--Interior of Salisbury Cathedral, Looking towards the North Transept (1805, pencil and watercolor on paper)

I thought I'd add another watercolor, because he did do a few architectural studies. They're astonishingly precise to the point of being almost mathematical. I assume therefore these were done more for posterity or educational purposes than for pride or celebration like the castle scenes.

--The Shipwreck (1805, oil on canvas)

Here is that battle again between humans and Nature. Nature was the victor this time, and it's the personalities of the survivors that become the focus. Looking up close, his brushstrokes are somewhat loose. He didn't go in with a tiny brush and render every individual eyelash. But that's one of the things that I found impressive, because despite these broad strokes of color, he was still able to get a sense of expression and gesture. You can really feel the fear and agony of this experience, and you go in closer, you get nothing more and yet, it's somehow still there.

--Sheerness as Seen from the Nore (1808, oil on canvas)

A little bit more calm, this one, but there's still a great tension. First of all, the huge ship in the background is tied very intimately to the little sloop in the foreground. The cloud formation forms this direct line from the sail of the sloop right down to the deck of the ship. The ship's rigging is a rhythm of diagonal lines almost exactly parallel to the pitch of the smaller boat. In contrast to all these sharp lines are the sweeping, swirling textures of the sea and sky, i.e. the elements, Nature again. So small and large, we get a camaraderie amongst the seafaring and the precariousness of that life. This story is nice enough, but then he adds the dinghy in the foreground, which allows for visible characters to give the whole thing personality.

--The Temple of Jupiter Panellenius, Restored (1816, oil on canvas)

I'm glad I was able to finally find such a large .jpg of this, so you can really see it, because I liked this one a lot. He's started bringing in these sort of classical themes, which seems entirely different from the hard gritty realities of life on the sea, almost like he felt he needed a little fantasy in his life. There's this fantastic relationship between the temple in the background and the revelers in the foreground, by way of that grouping of trees in the center. So check this out:

And specifically this:

But my favorite is this one:

I'm not making this stuff up. So there's a connection between the people and this glorious temple they've constructed (as it may have looked when it was first built), the majesty of human creativity. There's a connection between the temple and the beauty of nature itself, and another between the revelers frolicking in nature being a part of their land.

--The Field of Waterloo (1818, oil on canvas)

I wish I could've found a larger file for this, because it really is a stunning work. There was a gallery guide discussing this piece for a huge group of visitors. I didn't listen to all that much of what she was saying because I was following my own pace. But she said that victory has been achieved, you can see the fire blazing over to the right, and it should be a cause for celebration. Perhaps the folks in the foreground are glad it's all over, but what she was drawing attention to is that sharp, ominous moonlight making the whole scene very eery. She went on to point out that light, itself, becomes a major character in Turner's work, and was used very purposefully.

--Raby Castle, The Seat of the Earl of Darlington (1818, oil on canvas)

What a majestic expanse of the world this earl had at his disposal. This is also unfortunately small, so clicking it probably won't help much. But I loved the vantage Turner chose for this one. Aside from the sheer impressiveness of that lush, wide open field, it's all about how the clearing in the trees at center so rhythmically punctuates the towers of the castle. Again, there's a very strong connection between the Earl's residence and the land it oversees. The castle becomes a smoothly integrated part of the landscape, and at one with it.

--The Bay of the Baiae, With Apollo and the Sibyl (1823, oil on canvas)

I wanted to show you this one because there's a little bunny in it!

Heehee. Oh yes, I know, it's a very, very seeerious museum exhibition, so I'm not allowed to have any fun.

--The Battle of Trafalgar, 21 October 1805 (1824, oil on canvas)

This was my favorite piece in the whole show. It's absolutely unbelievable. The placement of it on the wall is really superb. The horizon line of the ocean is just about at eye level, so you're looking out over the water. But this painting is eight and a half feet tall, so there's literally another seven feet of painting towering up over your head. No jpg or reproduction could ever possibly do this any justice. The scene goes back out over miles and miles of Cape Trafalgar.

And that battleship. That battleship has four stories of gundecks, 104 cannons in all. It towers up over the water like a colossal floating fortress. It's the HMS Victory launched in 1765, and it still exists as a museum in Portsmouth. It's almost 230 feet long, displaces 3500 tons of water, and its tallest mast soars 205 feet into the air. Its oak hull is two feet thick. Just look at the stern of it:

It looks like a freaking office building. Those captain's quarters are bigger than my whole apartment, and I mean a LOT bigger. Can you tell I'm impressed?

Never before had I been so struck by the incredible power and size and fortitude of the Royal Navy. It's no wonder they were so very proud of it, and no wonder they ruled the seas for so long. And I owe that to Turner. The statistics are astounding, but it's really the artist's ability to capture the awe-inspiring scale of this battle that allows me to feel its immediacy. The painting is virtually in motion; you can practically smell the saltwater and burning wood, hear those giant canvas sails flapping in the breeze, the cheers of the British sailors. I might even be able to recommend seeing the show for this piece, alone.

--Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus (1829, oil on canvas)

As Ulysses sails away from the island of Cyclopes, he finally admits to Polyphemus that it was he who had gotten him drunk and blinded him. Polyphemus is furious, and prays to his father, Poseidon, to produce dangerous seas for Ulysses' journey.

Turner had begun exploring not just classical themes, but mythological ones, as well, late in his career, but this one was really very strange. All of his other work was so rooted down in hard reality, to the point of being a quite accurate record of historical events, as with his series on the burning of the houses of Parliament. Even Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus, hinting perhaps at Poseidon's supernatural powers, is still more or less a realistic reconstruction of a described event. And then...sea monsters? It's such an abstract piece as well, but the monster looks almost goofy. It makes me wonder if Turner wasn't losing his mind in his old age.

Since it is so very large, one critic recommended going through the show quickly one time and then going back for a longer look at the pieces that really grabbed you. My strategy was to concentrate on his oils and not spend an awfully long time on the watercolors, as I mentioned above. It worked out well for me, and certainly you could do the opposite if you're a huge fan of watercolor. In any case, this is another highly recommended show.

©2008, Ryan Witte

No comments:

Post a Comment