Another of the shows I haven't really had a chance to mention until now was the Armory Show. It was at the concurrent sort of sister show, Volta, where I found the work of Ian Davis. I was fascinated by his scenes and asked him for an interview. Here it is, for your enjoyment.

Ryan Witte: First of all, where do you call home?

Ian Davis: I live in Jersey City.

RW: Do you have a studio there or somewhere close by?

ID: My studio is in Hoboken. I've been there for the last six years but don't recommend it. I've had a great deal on a subsidized apartment in Jersey City, but apart from that it has no perks whatsoever for artists. I'm actually moving upstate at the end of this month, into a house that was built before the Civil War, with a studio in the back yard.

I'm looking forward to it.

RW: Wow, that sounds incredible. Although those old houses can tend to get a bit dusty.

Do you have music playing while you work?

ID: I listen to music constantly. That and NPR, like everybody else.

RW: What kind of music will you usually listen to?

ID: All types of music. For the last couple years, it's been lots of '60s psychedelia, mostly West Coast and English stuff. I'm interested in the way music from that era was crafted. It was weird, sonically, but the song was still important. I think that relates to my work in some way: this idea of things being a bit bent, a bit skewed, but it's still defined and articulated.

RW: I can totally see that, especially with some of Pink Floyd's really early work. I have this whole weird theory about what happened to music during that time, mostly revolving around John & Yoko's Life with the Lions that I won't bore you with--have you heard their first few solo records? But in my humble opinion, after around that time, the entire way music would be conceived and composed changed so dramatically.

ID: I'm really interested in recordings as opposed to performances. The thing about this music from roughly '66 to '68 is that people started making records that couldn't be performed. The drums are slowed down to give them a certain texture, the guitar is recorded over the drums, but is played by a guy standing in a field, and you get ambient noise behind it, there are backwards harpsichords, etc.. A lot of this music has very childlike sentiments, but there's a darkness there, as well. The Beach Boys made an amazing record called Smiley Smile that has a lot of the feeling I'm thinking of. It sort of creates its own little world.

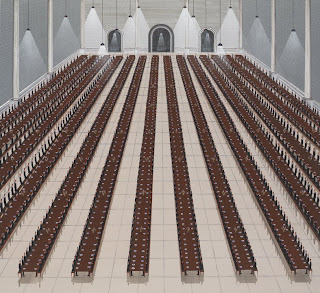

Ian Davis, Auditorium (2006, acrylic on Masonite)

RW: I notice you seem to prefer working on linen, and only one of the pieces I saw was on Masonite. Because of the kind of work you do, I'd actually think Masonite would be ideal. What is it you like about working on linen?

ID: The supports are just sort of what I have around. Somebody gave me a huge amount of linen, so I'm using that. Masonite is good, but big panels are really cantankerous, so I pretty much avoid using them for anything large. To be honest, I can't really tell the difference between linen and canvas, because once the surfaces are prepared and gessoed and sanded a million times, they act the same. Maybe if I were a different type of painter, there would be an advantage to one or the other, but for the way I work, it's pretty much the same.

Climate (2008, acrylic on linen), click to enlarge.

RW: Do you calculate your perspective by some geometric method or do you work it out by eye?

ID: The way I deal with perspective is anything but scientific. I'd describe the method I use as "good enough."

RW: [LOL]

ID: In other words, I typically decide while I'm making the painting what elements need to be correct-looking for the space to feel somewhat believable, but then I often contradict the perspective in places, so things don't look too static--a little off-kilter.

I use the most low-tech methods for putting things into perspective. It's a little embarrassing. If a painting is big, I have to calculate more (I use the term "calculate" loosely). A lot of masking tape is used. I try not to make things look too settled. But when I'm working out perspective, I'm using sticks and ropes and tape and all sorts of devices. Whatever works. It's not typically a mathematical thing, like Piero della Francesca or something.

RW: So halfway through, they look like one of those Jasper Johns pieces with all kinds of wooden bars and strings hanging off them?

ID: When the paintings are in progress, they look like a mess. I have to rope them in. They're built the way they look, and it's not until I'm about eighty percent done that they start to look like a painting, at all.

Dining Hall (2009, acrylic on linen)

RW: The spaces your subjects occupy are enormous and a few have no visible ceiling. The ceiling in the Dining Hall, for instance, would have to be at least ninety feet high, if not higher. Does being framed by the proportions of a painting guide or distort the environments in it, or do you proportion your paintings to accommodate what will be in them?

ID: The relationship between the spaces and the figures is pretty much worked out on the fly. Sometimes I want architecture to dwarf the people. Sort of like the way the architecture dwarfs Anthony Perkins in Orson Welles' The Trial--this idea of the institution dwarfing the people.

Court scene begins at around 3:45.

I really like the way scale is used in that movie.

RW: It's interesting that you mention that here, because Citizen Kane was remarkable for being one of the first films to ever show ceilings in its interior shots. Most Hollywood movie sets didn't have them so they could be lit more thoroughly, but Welles insisted for artistic reasons.

ID: I wasn't aware of that about Citizen Kane, although I love the movie (obviously) and wasn't aware of some of the lengths he went to to get what he wanted to see. Have you seen The Magnifent Ambersons?

RW: No, I haven't, but I think the man is a genius, and I really should see more of his work.

ID: That's a really good one, too. I don't know why you can't get it anywhere.

RW: Maybe because the final release was so mangled beyond recognition by the studio? It may be too far from Welles' original vision to be of as much interest to his fans as the others.

Anyway, to get back to your paintings...

ID: The sizes of the paintings are not exactly arbitrary, but I don't fuss about it a lot. Occasionally, I'll start a painting and realize that it needs to be bigger and I'll start it over somewhere else. Typically, I'll just fill up the surface of whatever I have.

RW: This is probably a very obvious question in regard to your work, but do institutions breed uniformity?

Guilded Age (2008, acrylic on linen)

ID: I'm not sure that institutions breed uniformity. I hate to take a definitive position on that, but I'd say that that's pretty much the objective of most institutions. I'm just not sure that uniformity is always a bad thing. Usually I'm taking a critical look at some really basic characteristic of human nature such as greed, or opportunism, or conformity.

Excavation (2008, acrylic on canvas)

RW: The gaze of your subjects also seems to be always very limited in scope (to only whatever happens to be lit by the light on their helmets) or focused on one single point in space, one fetishized object. Is there something dangerous about their inability to grasp a bigger, more complete impression of their surroundings?

ID: I think of the figures in my paintings as people who have lost their ability to do anything other than go along with it all. Occasionally there will be a few people sneaking sideways glances, but for the most part they are participants. They stare at a fixed point because they have been told to.

RW: I'm curious about these sideways glancers. Are they checking to see what everybody else is doing so they can properly conform, or perhaps making sure everyone else is doing what they're told, or are they renegades?

ID: I really don't know about the sideways glancers. When I'm painting a crowd, I'm just sitting really close and not stopping to look much. It happens better if I don't constantly check my progress. Occasionally, some of the people are looking at each other accidentally. Sometimes I'll paint a guy and he looks just like my ninth grade geometry teacher or some actor or something. There's a little pause, "oh, I just painted Jan-Michael Vincent..." something like that. Just little accidents. If I were too conscious of doing all this repetitive stuff, I'd never get anything done. A lot of these paintings just become what they are by the virtue of being painted. I think some of the mystery or darkness might just be inherent.

Physicians (2008, acrylic on linen)

RW: Is the culture of institutions somehow self-defeating? In other words, does the necessity to focus resources on one goal or another prevent them from solving the problems they face in a more efficient manner?

ID: I don't really know about the culture of institutions. I don't have a fixed perspective on that. I tend to look at all clubs critically, but I suppose that they are necessary to get things done. I think it's easier to focus on fixing one thing rather than trying to fix everything. I'm just skeptical, because I'm a bit more attuned to observing man's destructive objectives, and how they are often carried out under the guise of "progress."

Strategy (2006, acrylic on canvas)

RW: In the broadest possible sense--that is, divorced from militarism--what constitutes an "army"?

ID: I would describe an army as a group of obedient people who do not function as individuals. But again, I certainly don't consider myself an authority on this, since I've never been in an army. I'm just trying to create masses rather than individuals.

Corporation (2006, acrylic on canvas)

RW: Is corporate culture inherently detrimental to human beings and/ or the planet we inhabit?

Clients (2008, acrylic on linen)

ID: I think corporate culture is repulsive and destructive and requires its participants to feign ignorance of the effects of their actions on the world around them. I don't think this is inherent to corporations, but as long as the accumulation of wealth is the only goal, then everything else becomes insignificant.

Banquet (2006, acrylic on linen)

RW: Have you ever worked in a 9-to-5 cubicle job?

ID: I have always avoided the 9-to-5. When I was eighteen and knew nothing about being an artist, I read a book on Keith Haring where he explained that you can't be an artist unless that's all you're trying to be, which I took very much to heart. I didn't really start painting seriously until I was twenty-one, however. I never had a desire to do any work other than my own.

RW: Do you hope your paintings will be perceived as "beautiful"?

ID: I definitely want my work to be beautiful. That's really important to me. I suppose it's my idea of beauty that might be a bit peculiar. But I'm interested in making a beautiful object. This isn't the only goal, obviously, but I'm interested in a dark sort of beauty.

RW: I definitely think you succeed. But it makes for a strange contrast in your work. While the pieces are formally very pleasing to the eye, the scenes you depict are somehow unsettling and a little bit creepy, which I take to be on purpose...

Thanks, Ian!

Ian Davis is represented in New York by Leslie Tonkonow Artworks:

www.tonkonow.com

212 255 8450

©2009, Ryan Witte