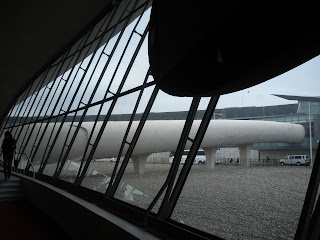

In celebration of Halloween today, I'd like to make an addendum to my series on JFK Airport and talk about my very first time seeing the interior of Eero Saarinen's TWA Flight Center. I've honestly lost count of how many times I'd been out there and couldn't get inside it. On various trips I didn't realize it'd been closed or had heard it had reopened and it hadn't. In fact, on this trip out, I thought I had heard the restorations had been completed, but they haven't this time, either. Presumably I'll have to go out yet again when it has been completely finished and reopened. What they meant, I suppose, is that the restoration of the main central lobby space is done, which it is. It's not open yet, but the doors were unlocked for Open House New York a few weekends ago.

I did look through music from 1962 in preparation for this visit, but I

didn't have the time to rip all those songs into my computer. Instead I just

loaded up Latin-esque

by Juan Carlos Esquivel onto my iPod. It seemed fitting. There was one

song that came out in late August, 1962 that I've always found somewhat

irritating, but it's just too perfect

to not mention it in this post. Apologies for the "Pickroll" if anyone

feels the same. Amusingly, it may actually be the first song in history

to include the sound of a bong hit.

I had seen innumerable photographs, seen floor plans and drawings, studied the model extremely carefully. Nothing came as a huge surprise. On top of that, although it may have been extremely complicated to construct, it's rather simple in form, in the ways that would matter. It's almost perfectly symmetrical. So one nice coincidence is that I'm able to quote one of my top ten movies of all time, Stanley Kubrick's The Shining (1980) on Halloween: "...it was as though I'd been here before. I mean, we all have moments of deja vu, but this was ridiculous. It was almost as though I knew what was going to be around every corner. Ooooo!" It was still magical to finally be inside what I consider to be one of the most incredible works of architecture of the entire twentieth century.

It is starting to look really beautiful, too. Already it looks noticeably better than the last time I walked around the outside of it. It sounds as if they're going to try to restore much of it back to the period when it was in its heyday as a monument to air travel, from around 1962 to 1969. So all the restaurants and cafes should look extremely groovy. They're also going to retain all reminders that this was once a TWA building. In other words, all the TWA signage will not be replaced by signs for jetBlue. They have a long way to go, but as Saarinen himself said about it being a "beautiful ruin," even in its decrepit state, barely any imagination is required at all to see how fabulously Space Age a work of architecture this is. Evidently the ticket counter wing is going to be converted into a hotel. If they do that right, staying the night there could make it totally worth having your flight cancelled.

Happy Halloween fellow architecture lovers!

All text and photos 2012, Ryan Witte.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Sunday, October 14, 2012

The Legends of an Apostle

On some level, I've been researching this post for over twenty-five years. For at least the past five or so, it's been a dream of mine to finally put it together. At around twelve years old, I moved into a house less than about 500 feet from this one. I was instantly fascinated by it. Over the next five years after that, I gradually heard more and more of the legends surrounding the house. Then I became fairly good friends with a niece of the family who owned it. While she was staying with them for a short time, I got to see the inside of it. It's possibly one of the most magnificent places I've ever been. The Victorian mansion at 40 Hilton Avenue in Garden City, New York, was designed by architect John Kellum and was likely completed shortly after Kellum's death in 1871.

Helping the integrity of the house enormously is a wonderful collection of antique furnishings, more or less from the correct era, that the family has found to decorate it. My host told me they'd always loved antiques and scoured shops all over for just the right pieces. One of the period pieces they found is a huge antique music box. It's the size of a small cabinet and

plays enormous notched metal disks, maybe around a foot and a half (half a meter) in diameter. When I first saw this thing, having

always been fascinated by elaborate mechanical devices, I thought it truly was one of the coolest things I'd ever seen. Of course I'd seen

nickelodeons, but I'd never seen anything quite like this before. I was excited to see that it's still there in their hall.

Speaking of music, I did something in preparation for this story that I've been thinking about doing for my more historical posts for a while. I had an added incentive for putting it together more seriously this time. I presented it to the owners on a CD as a gift of thanks for their hospitality. The question I wanted to answer was, when the house was finished and the first family moved in, if they were to have a housewarming party, what would the music have sounded like? I went back one year for compositions to travel around Europe gaining popularity, then another two years for that music to cross the Atlantic and gain popularity in the United States. I sought out particularly Chamber Music from the years 1868-1871, what could realistically be performed by a pianist, a quartet of musicians, and/or a small group of singers in the house's drawing room.

This proved a bit too limiting, especially where the dance music was concerned, so I allowed for performances by larger ensembles which presumably any halfway decent professional quartet could have distilled down into a chamber orchestration. Another exception is Von Weber's "Invitation to the Dance" from 1819 which remained popular throughout the middle of the nineteenth century. Hector Berlioz' orchestration of it in 1841 would have kept its popularity surging further. The songs are divided into sections of the evening: the arrival of the guests, dinner for close friends, the young lady of the house sings a song, the remaining guests arrive for dancing, singers arrive, more dancing, and the guests departing. I wasn't able to find a few of the more obscure selections, but the ones I could I've compiled into a YouTube playlist, which you're welcome to listen to while reading the rest of this post to get in the mood.

The Victorians were very serious about their parties. Every household throwing a party was determined theirs would be bigger, more elaborate, and more spectacular than the previous house party in town. There was a whole litany of behavioral rules and regulations and protocols.

The architecture reflects this regulation of behaviors. Everything in the Victorian home had its own particular place. The people occupying them did, also. Unlike smaller homes which don't have the luxury of size, in a larger house like this one, everything and everyone could be sequestered by gender or class into specific spaces to enforce those protocols. It was just not thought appropriate for certain members of society to interact with others in a manner that wasn't tightly controlled. The front parlor, for instance, was often considered a female space and would have been decorated as such. Men were free to enter whenever they wished. The billiard room, smoking room, or study was considered a male domain, and it was seriously frowned upon for women to enter unless for very specific reasons.

In comparison to the open plans of suburban homes in the 1950s and 1960s, the spatial division in Victorian houses reflects the highly regulated, socially formalized period during which they were built. So while the family residing in the house would use the main staircase in the hall, servants were delegated to a service staircase leading up from the pantry at the back of the house. I say "pantry" because my host told me that originally, the kitchen had been in the basement. From what I've learned, this was not unusual, in fact in a lot of homes especially prior to when this one was built, the kitchen would often have been located behind the main house in a separate structure altogether. Kitchens were smoky, smelly, and painfully hot in the summertime, but most importantly had a terrible knack for regularly burning down to the ground.

In a way, it's odd to contrast the Victorian era's strict division of interior space with the open plan of the 1950s, because as discussed earlier, both periods shared a highly formalized social structure. Although the open plan was pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright many years earlier, it wasn't adopted in huge numbers for suburban homes until the social protocols started to fracture in the late-1950s. Its wide-spread adoption was also in part a result of, and incorporated, a lot of psychology and (occasionally quasi-)scientific examinations of efficiency in house designs carried out through the 1930s, particularly where it concerned the kitchen.

Furthermore, 40 Hilton is larger in scale than most middle-income suburban houses that would have utilized the open plan. Many larger houses even in the 1960s, especially ones built to both require and accommodate domestic help, would have worked from a noticeably different model. The 1950s housewife was the center of domestic life in her home, responsible for its maintenance and operations whether she wanted to be or not. The upper-class Victorian housewife, on the other hand, was more of a mere ornament in her residence. She would very rarely even have set foot in the kitchen for anything other than to give orders to staff, whereas that same space would be the center of command (and/or imprisonment) for her mid-twentieth-century middle-class counterpart.

The first Main Line of the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) to Hicksville--including the Mineola train station--was in full service by 1837. Two years later, the first branch off the Main Line led from Mineola through what would become the town of Garden City into Hempstead, a line which no longer exists (roughly following the path of Franklin Avenue, parallel to Hilton immediately to the east). In 1869, a multimillionaire named Alexander T. Stewart purchased a huge plot of grassy land in Hempstead Plains bounded by Mineola to the north and Hempstead to the south, Floral Park to the west and Bethpage to the east. In the middle of this he founded the village of Garden City and opened up a train station with the same name on the LIRR Main Line.

It was the single largest land purchase of the century in the United States, a plot of land about two-thirds the size of the entire island of Manhattan, by a man calculated by today's standards to have been the sixth or seventh wealthiest man ever to have lived in this country. His town would be the first planned community here based on the garden city movement championed in England by Ebenezer Howard. The same movement, coincidentally, would be employed in my own neighborhood of Sunnyside, Queens, in the 1930s. In 1872, Stewart completed his Central Rail Road branch from Flushing, stopping at a new Garden City station at the center of the village, and on out to Farmingdale. One small branch from this line led from Bethpage Junction to Bethpage, where Stewart had a brickworks that would supply building material for all the community buildings in his new village. The original Garden City station on the Main Line was then renamed the Merillon Avenue station.

Most of the first houses to be built in Garden City were by John Kellum. He'd designed Stewart's cast-iron department store at Broadway and Tenth Street (1862)--the country's first department store and the largest retail store in the world at the time--and his palatial residence on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Fourth Street (1869).

There were ten of these large Victorian houses built, all of them

identical aside from their porches which were always oriented to the

south. Two of them remained under the ownership of nearby schools, St.

Mary's and St. Paul's, into the 1970s. For a short time they housed

students of the schools, who nicked-named them the "Apostles." There are

six Apostle houses left, of which 40 Hilton is one. A number of smaller

houses to follow were nick-named the "Disciple" houses. Not much of Kellum's work appears to still stand in Manhattan aside from one notable structure, the Tweed New York County Courthouse (1861). He was evidently a huge fan and also something of a master of Victorian architecture.

There were ten of these large Victorian houses built, all of them

identical aside from their porches which were always oriented to the

south. Two of them remained under the ownership of nearby schools, St.

Mary's and St. Paul's, into the 1970s. For a short time they housed

students of the schools, who nicked-named them the "Apostles." There are

six Apostle houses left, of which 40 Hilton is one. A number of smaller

houses to follow were nick-named the "Disciple" houses. Not much of Kellum's work appears to still stand in Manhattan aside from one notable structure, the Tweed New York County Courthouse (1861). He was evidently a huge fan and also something of a master of Victorian architecture.

In a way, it's ironic that I am a fan of this style, too, since what I tend to discuss most here is the movement that arose specifically out of intense distaste for the Victorian age architecture and its rampant eclecticism. But I'd also like to say that I think the subject of this post is an impeccable example of Victorian architecture, mostly because it is most certainly grand and ornamental, but not in the overblown ways some mansions of the era were, as if every lathe within hundreds of miles had to be employed to finish the job. Its proportions and detailing are stately and refined. It also doesn't hurt at all that the current owners (my school friend's relatives) have done an admirable job of restoring the house as sensitively as was possible and diligently maintaining its splendor.

Perhaps it would have been different had I been a total stranger. My strikeouts at the Libeskind house and also attempts to see Wallace Harrison's beautiful Modernist estate in Huntington are two great examples of the difficulties involved in looking at privately-owned homes. It was still relatively rough working out the logistics with the current owners and hoping that the weather reports would be accurate. But I'll have to say that the family could not have been more welcoming and hospitable. Many, many thanks to them for their warm reception, accommodations, and shared information. I'd also like to thank Garden City historian John Ellis Kordes, who spoke to me on the phone and was incredibly forthcoming and helpful.

In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibited the sale of alcohol. This, the loosening of morality of the early twentieth century, the rise of Hollywood cinema as the dominant art form, and the spread of organized crime surrounding the homespun manufacture, bootlegging, and sale of alcohol gave birth to an entire underground subculture in this country. The prime focus of nightlife during this era was often quite literally under ground, the Speakeasy. Saloon owner Kate Hester continued to run her establishment in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, without a liquor license after the cost of them was raised exorbitantly in 1888. In order to not draw attention to the unlicensed saloon, she would tell patrons who got boisterous to "speak easy, boys! speak easy!"

In New York City, Speakeasies were also in part responsible for the spreading popularity of Jazz and the birth of the Charleston. Their most visible character was the free-wheeling Flapper. The quintessential Flapper, in my opinion, will always be Louise Brooks. Prior to Prohibition, mixing good spirits with anything else had typically been considered bad form, but since the neat liquor during Prohibition was often of such low quality and questionable taste, cocktails became a new fad.

During this time, the owner of 40 Hilton was also the manager of the majestic Garden City Hotel nearby. The rumor goes that since it was no longer legal to serve alcohol at the hotel, sometime probably around 1923-25, he decided the best solution was to build a Speakeasy in the basement of his own home.

The irony of installing a Speakeasy in a Victorian house cannot be easily overstated. Speakeasies, Jazz, and the Flappers who enjoyed them were rejecting anything and everything Victorian society had held dear. The Flappers were wild and sexually liberated; they referred to a wedding ring as a "handcuff." They followed Coco Chanel's lead and cast off the formal (and uncomfortable) bustles, corsets, pantaloons, and petticoats that restricted their movement for the freedom of short, slinky dresses amounting to not much more than a short satiny slip held up by spaghetti straps with maybe some fringe at the bottom. They smoked, drove cars, cropped their hair short, and rebelled against all the gender protocols of earlier eras. Jazz itself was sort of the Hip-Hop of its day. It was all very Punk Rock in its way, and quite badass. Certainly many Speakeasies were high-class establishments requiring black tie and tails and employing less controversial musicians. Perhaps this was more the vibe in the basement of 40 Hilton, but the historical conflict remains, in principle.

The bar room proper is actually incredibly small. No more than about five drinkers could comfortably occupy it at one time. This small room has a door with the requisite peephole on the door, through which the proprietor could see who was requesting admittance and demand the secret password. Outside this is a larger room with the billiard table and a working fireplace. I only asked if it were functional because it seemed strange to me that there would have been a fireplace in the basement at all, until I learned that it originally contained the kitchen. The house has three flues, impressively; this is one. Due to the diminutive size of these two rooms, presumably it was really enjoyed only by personal friends of the hotel's manager and V.I.P. guests at the hotel personally invited to it by him.

Whether or not the owners of the house at the time had connections to organized crime, I'll not speculate, but for sure an illegal bar could never have lasted long without that, an insider connection with the local police department, or at the very least, enough money to bribe constables to look the other way (although there were only two of them). There is still something in the basement that may very well have served as an alarm. In a small nook near the ceiling in a corner of the billiard room, there's this old-timey looking siren. My host said they never quite knew what it was or what it was for. My best guess is that there was a button somewhere on the first floor near the entrance that could set off this siren when the police arrived to bust up the merriment. Oddly, I'd think something as loud as a siren would be heard all through the house, including at the front door, so who knows?

It's incredible enough that there's a Speakeasy there at all, but another piece of the legend makes it all the more fantastic. The rumor was that there was a tunnel dug from the Garden City Hotel two rather long blocks away to the basement of this house so guests could visit the Speakeasy privately. When I visited the house with my friend all those years ago, she showed me this arched cement portal (now containing bookshelves) in the basement that faces the direction of the hotel. At the time, we both agreed this must certainly be the entrance to the infamous tunnel.

On this more recent visit, my host assured me that behind this arch, an alleged tunnel would have had to cut through the extant coal chute, rendering it impossible. He also said that a village historian visiting the house had scoffed at the idea that any such thing ever existed, to his knowledge. With all respect to my host and appreciation for realistic skepticism, I have far too wild and romantic an imagination to ever fully believe there was no tunnel and that that cement arch isn't what remains of it. I'd have gotten a photo of it so you could decide for yourself, but the current family uses their basement for storage as many of us do, and one of my top priorities was to not intrude on their privacy.

Another argument for this story being mere legend is that it would seem an outrageous waste of resources to construct such a tunnel. But Garden City is, and no doubt was then, a conspicuously conservative town. Add to this what is the only four star hotel on Long Island (according to them). Vanderbilts stayed there, Astors, Morgans, Guggenheims, Theodor Roosevelt, John and Jackie Kennedy, Margaret Thatcher, Henry Kissinger, Sarah Ferguson, Hillary Clinton, and Prince Khaled of Saudi Arabia. Perhaps most famously, due to the hotel's close proximity to Roosevelt Field Airport (now a huge shopping mall), Charles Lindberg stayed at this hotel the night before his transatlantic flight in 1927. The point is, these are the type of folks who would not want to be seen strolling down the street from their hotel to what everyone suspects is an illegal drinking hole, especially in a heavily religious community. They'd want to be far more discreet. A suburban residential neighborhood typically doesn't have dark back alleys for slinking into a Speakeasy unnoticed.

The village had a population of only around 2000 at that time, most of them devout Episcopalians forming a congregation for the enormous and majestic Cathedral of the Incarnation (Henry G. Harrison, 1885) a few blocks away. The cathedral and bishop's residence, the schools, and other public buildings were all served by large underground pipes from a centralized heating plant near to the present location of the town's middle school (typically years six, seven, and eight). Oddly, I still remember there being random manhole covers in the school's sports field, but never knew that's what they were. It was also rumored that these pipes were used by boys at St. Paul's to sneak over to visit the girls at St. Mary's, but this was also nothing more than legend. But this may have been what evolved into the legend of the Speakeasy tunnel. Moral of the story, this particular tunnel may never have existed, but I would just really love to believe that it did. Someday perhaps an archeological excavation will reveal the truth.

I'd also much rather believe that Lindberg actually did stop off for a Gin Rickey or two at this Speakeasy than to think he preferred to "get a good night's rest," although it's unlikely the eve of his historic trip was his first or last time at Roosevelt Field or staying at the hotel. He may have been a regular, in fact. My host did tell me that evidently the president of Ford Motors drank at the little basement bar some time in the 1950s, when holding that post was Henry Ford II. I'm not sure what I'm supposed to make of this synchronicity, but there is actually an old photograph showing Henry and Edsel Ford, subject of a relatively recent post here, with Lindberg, who appears in this post.

It is possible that the basement bar remained in use as a modest nightspot into the mid-1930s--although I rather doubt the owners at the time would have wanted anyone other than close friends in their private home once it was no longer a social and legal necessity. Without question, if there ever were a tunnel, it would have been sealed off shortly after Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

The first Garden City Hotel was designed by John Kellum in the Victorian style and built by Alexander Stewart in 1874. In 1895, a much larger shell was wrapped around the earlier structure with white-trimmed, red-brick Georgian Revival architecture by McKim, Mead, & White (MM&W). This one burned down after only four years, and the most famous of the buildings on the site, a much larger Georgian masterpiece also by MM&W, opened in 1901 with a cupola based almost precisely on the one on top of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Stamford White was married to Bessie Smith, who was Stewart's wife's grandniece. The firm of Ford, Butler, & Oliver matched MM&W's style to expand the two wings in 1911, but other than that, this is the structure which was rumored to have had a secret tunnel to 40 Hilton.

The hotel quite tragically went bankrupt and this incredible structure was demolished in 1973. From 1973 until 1980, it was an unassuming one-room building by an unknown architect. It was then rebuilt and reopened at a larger size again. The interiors, with antiques personally selected in Europe by the owner's daughter, Cathy Nelkin, are appropriately luxurious, but the exterior is entirely forgettable, especially compared to its earlier manifestations. In fact, no one anywhere seems to have any idea of the identity of the architect or architectural firm responsible for its present design.

Sometime before the current owners purchased 40 Hilton in around 1986 or so, an owner of the house had removed the staircase leading from the third floor to the cupola or "widow's watch" on the roof, replacing it with a closet. That term, by the way, comes from the tale that the widow would use a cupola like this to go up and watch for her husband lost at sea returning home again.

The cupolas on the Apostle houses had a tendency to easily rot. As a result, most of them were removed. That along with the refacing of exteriors on some of them and other alterations over the years makes it almost impossible now to see that they were all once identical. Since their cupola was rotting as well, the former owners of this house just sealed up the opening in the ceiling. I suppose I'd like to blame the 1970s for this, a decade relatively unkind to architecture. But in fairness, before the advent of double-glazed windows, the cupola likely sucked all the warm air right up out of the house in the wintertime, even with the door closed.

My host told me that, thankfully, they needed to make very little structural improvements to the house. He said the previous owners had chosen relatively accurately Victorian wallpapers and decor, but that a lot of the colors were rather dark (as Victorian rooms often were). They lived with it for a while before deciding it was time to brighten up the house a bit. He also said they might have gone a bit further in their restoration, but could find absolutely no original floor plans for this house anywhere. One of the more involved restorations they undertook was to open up the cupola again, install a fold-down stair as you'd see accessing an attic, repair the rotted cupola itself, and create a roof deck surrounding it. It was really quite stunning up there--this house is one of the tallest buildings around. I was sort of hoping to see the hotel from the roof, but the hundred-year-old trees in the neighborhood are taller than anything else, including this house.

For some unknown reason, after the cupola was reopened, the house began to experience some strange phenomena. My friend from school told me that she'd be coming down the main grand staircase and see the door to the powder room under the stairs opening or closing in the reflection in the mirror on the opposite wall. But everyone in the house would be in the kitchen or dining room, none of them using the powder room. Oooooooooo... The toilet in there would be heard randomly flushing, as well, even though no one was in there. I'm not saying I necessarily believe in these sorts of things or not, but if I did, it wouldn't surprise me to learn of it happening in a house like this, with such an incredibly rich history.

That the strange occurrences seemed to coincide with the opening of the rooftop cupola is a bit odd, because I'd think the characters to be found in the Speakeasy downstairs would have been a lot more colorful than some demure Victorian girl. Speakeasy patrons could use a restroom in the basement, however. My friend had also shown me that in one of the bedroom closets, there's a small, maybe four-foot-high door (a little over a meter high) leading to some kind of secret passageway. Where it led, she'd never known. My host said it merely leads to one of the other bedrooms, but just the idea that there would be a secret passageway in this house is so delightfully perfect.

My friend and I were somewhat Goth at the time (my excuse is that we were seventeen), so the whole experience was a bit like hanging out with Lydia, Winona Ryder's character in Beetlejuice. Granted, my friend was considerably more upbeat and fun than Lydia Deetz, so I mean that in a very, very good way. I think the enthusiasm of this post proves that well enough. The current owner seemed to suggest that there hasn't been too much mysterious toilet flushing for a while, but he told me that when it does happen, it always seems to be right around this time of the year.

While I would be pleased to present this story to you at any time, I'm especially elated that it worked out in such a way that I could post it now, just as we near Halloween 2012. For readers who may live in other parts of the world, Halloween is the festival in the United States celebrating the deceased, although it's sort of evolved into something very different now. As a matter of fact, this story was completed a couple weeks ago. On the recommendation of a good friend to whom I told some of this story, I decided to wait and publish it much closer to the holiday. Not that the house at 40 Hilton is spooky in any way, mind you. In my opinion it's absolutely beautiful. If I were a ghost, I'd probably want to stick around, also.

All text and 40 Hilton photos ©2012, Ryan Witte.

|

| The antique music box is at bottom left. |

Speaking of music, I did something in preparation for this story that I've been thinking about doing for my more historical posts for a while. I had an added incentive for putting it together more seriously this time. I presented it to the owners on a CD as a gift of thanks for their hospitality. The question I wanted to answer was, when the house was finished and the first family moved in, if they were to have a housewarming party, what would the music have sounded like? I went back one year for compositions to travel around Europe gaining popularity, then another two years for that music to cross the Atlantic and gain popularity in the United States. I sought out particularly Chamber Music from the years 1868-1871, what could realistically be performed by a pianist, a quartet of musicians, and/or a small group of singers in the house's drawing room.

This proved a bit too limiting, especially where the dance music was concerned, so I allowed for performances by larger ensembles which presumably any halfway decent professional quartet could have distilled down into a chamber orchestration. Another exception is Von Weber's "Invitation to the Dance" from 1819 which remained popular throughout the middle of the nineteenth century. Hector Berlioz' orchestration of it in 1841 would have kept its popularity surging further. The songs are divided into sections of the evening: the arrival of the guests, dinner for close friends, the young lady of the house sings a song, the remaining guests arrive for dancing, singers arrive, more dancing, and the guests departing. I wasn't able to find a few of the more obscure selections, but the ones I could I've compiled into a YouTube playlist, which you're welcome to listen to while reading the rest of this post to get in the mood.

The Victorians were very serious about their parties. Every household throwing a party was determined theirs would be bigger, more elaborate, and more spectacular than the previous house party in town. There was a whole litany of behavioral rules and regulations and protocols.

The architecture reflects this regulation of behaviors. Everything in the Victorian home had its own particular place. The people occupying them did, also. Unlike smaller homes which don't have the luxury of size, in a larger house like this one, everything and everyone could be sequestered by gender or class into specific spaces to enforce those protocols. It was just not thought appropriate for certain members of society to interact with others in a manner that wasn't tightly controlled. The front parlor, for instance, was often considered a female space and would have been decorated as such. Men were free to enter whenever they wished. The billiard room, smoking room, or study was considered a male domain, and it was seriously frowned upon for women to enter unless for very specific reasons.

In comparison to the open plans of suburban homes in the 1950s and 1960s, the spatial division in Victorian houses reflects the highly regulated, socially formalized period during which they were built. So while the family residing in the house would use the main staircase in the hall, servants were delegated to a service staircase leading up from the pantry at the back of the house. I say "pantry" because my host told me that originally, the kitchen had been in the basement. From what I've learned, this was not unusual, in fact in a lot of homes especially prior to when this one was built, the kitchen would often have been located behind the main house in a separate structure altogether. Kitchens were smoky, smelly, and painfully hot in the summertime, but most importantly had a terrible knack for regularly burning down to the ground.

In a way, it's odd to contrast the Victorian era's strict division of interior space with the open plan of the 1950s, because as discussed earlier, both periods shared a highly formalized social structure. Although the open plan was pioneered by Frank Lloyd Wright many years earlier, it wasn't adopted in huge numbers for suburban homes until the social protocols started to fracture in the late-1950s. Its wide-spread adoption was also in part a result of, and incorporated, a lot of psychology and (occasionally quasi-)scientific examinations of efficiency in house designs carried out through the 1930s, particularly where it concerned the kitchen.

Furthermore, 40 Hilton is larger in scale than most middle-income suburban houses that would have utilized the open plan. Many larger houses even in the 1960s, especially ones built to both require and accommodate domestic help, would have worked from a noticeably different model. The 1950s housewife was the center of domestic life in her home, responsible for its maintenance and operations whether she wanted to be or not. The upper-class Victorian housewife, on the other hand, was more of a mere ornament in her residence. She would very rarely even have set foot in the kitchen for anything other than to give orders to staff, whereas that same space would be the center of command (and/or imprisonment) for her mid-twentieth-century middle-class counterpart.

The first Main Line of the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) to Hicksville--including the Mineola train station--was in full service by 1837. Two years later, the first branch off the Main Line led from Mineola through what would become the town of Garden City into Hempstead, a line which no longer exists (roughly following the path of Franklin Avenue, parallel to Hilton immediately to the east). In 1869, a multimillionaire named Alexander T. Stewart purchased a huge plot of grassy land in Hempstead Plains bounded by Mineola to the north and Hempstead to the south, Floral Park to the west and Bethpage to the east. In the middle of this he founded the village of Garden City and opened up a train station with the same name on the LIRR Main Line.

It was the single largest land purchase of the century in the United States, a plot of land about two-thirds the size of the entire island of Manhattan, by a man calculated by today's standards to have been the sixth or seventh wealthiest man ever to have lived in this country. His town would be the first planned community here based on the garden city movement championed in England by Ebenezer Howard. The same movement, coincidentally, would be employed in my own neighborhood of Sunnyside, Queens, in the 1930s. In 1872, Stewart completed his Central Rail Road branch from Flushing, stopping at a new Garden City station at the center of the village, and on out to Farmingdale. One small branch from this line led from Bethpage Junction to Bethpage, where Stewart had a brickworks that would supply building material for all the community buildings in his new village. The original Garden City station on the Main Line was then renamed the Merillon Avenue station.

Most of the first houses to be built in Garden City were by John Kellum. He'd designed Stewart's cast-iron department store at Broadway and Tenth Street (1862)--the country's first department store and the largest retail store in the world at the time--and his palatial residence on Fifth Avenue and Thirty-Fourth Street (1869).

There were ten of these large Victorian houses built, all of them

identical aside from their porches which were always oriented to the

south. Two of them remained under the ownership of nearby schools, St.

Mary's and St. Paul's, into the 1970s. For a short time they housed

students of the schools, who nicked-named them the "Apostles." There are

six Apostle houses left, of which 40 Hilton is one. A number of smaller

houses to follow were nick-named the "Disciple" houses. Not much of Kellum's work appears to still stand in Manhattan aside from one notable structure, the Tweed New York County Courthouse (1861). He was evidently a huge fan and also something of a master of Victorian architecture.

There were ten of these large Victorian houses built, all of them

identical aside from their porches which were always oriented to the

south. Two of them remained under the ownership of nearby schools, St.

Mary's and St. Paul's, into the 1970s. For a short time they housed

students of the schools, who nicked-named them the "Apostles." There are

six Apostle houses left, of which 40 Hilton is one. A number of smaller

houses to follow were nick-named the "Disciple" houses. Not much of Kellum's work appears to still stand in Manhattan aside from one notable structure, the Tweed New York County Courthouse (1861). He was evidently a huge fan and also something of a master of Victorian architecture. In a way, it's ironic that I am a fan of this style, too, since what I tend to discuss most here is the movement that arose specifically out of intense distaste for the Victorian age architecture and its rampant eclecticism. But I'd also like to say that I think the subject of this post is an impeccable example of Victorian architecture, mostly because it is most certainly grand and ornamental, but not in the overblown ways some mansions of the era were, as if every lathe within hundreds of miles had to be employed to finish the job. Its proportions and detailing are stately and refined. It also doesn't hurt at all that the current owners (my school friend's relatives) have done an admirable job of restoring the house as sensitively as was possible and diligently maintaining its splendor.

Perhaps it would have been different had I been a total stranger. My strikeouts at the Libeskind house and also attempts to see Wallace Harrison's beautiful Modernist estate in Huntington are two great examples of the difficulties involved in looking at privately-owned homes. It was still relatively rough working out the logistics with the current owners and hoping that the weather reports would be accurate. But I'll have to say that the family could not have been more welcoming and hospitable. Many, many thanks to them for their warm reception, accommodations, and shared information. I'd also like to thank Garden City historian John Ellis Kordes, who spoke to me on the phone and was incredibly forthcoming and helpful.

In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibited the sale of alcohol. This, the loosening of morality of the early twentieth century, the rise of Hollywood cinema as the dominant art form, and the spread of organized crime surrounding the homespun manufacture, bootlegging, and sale of alcohol gave birth to an entire underground subculture in this country. The prime focus of nightlife during this era was often quite literally under ground, the Speakeasy. Saloon owner Kate Hester continued to run her establishment in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, without a liquor license after the cost of them was raised exorbitantly in 1888. In order to not draw attention to the unlicensed saloon, she would tell patrons who got boisterous to "speak easy, boys! speak easy!"

In New York City, Speakeasies were also in part responsible for the spreading popularity of Jazz and the birth of the Charleston. Their most visible character was the free-wheeling Flapper. The quintessential Flapper, in my opinion, will always be Louise Brooks. Prior to Prohibition, mixing good spirits with anything else had typically been considered bad form, but since the neat liquor during Prohibition was often of such low quality and questionable taste, cocktails became a new fad.

During this time, the owner of 40 Hilton was also the manager of the majestic Garden City Hotel nearby. The rumor goes that since it was no longer legal to serve alcohol at the hotel, sometime probably around 1923-25, he decided the best solution was to build a Speakeasy in the basement of his own home.

The irony of installing a Speakeasy in a Victorian house cannot be easily overstated. Speakeasies, Jazz, and the Flappers who enjoyed them were rejecting anything and everything Victorian society had held dear. The Flappers were wild and sexually liberated; they referred to a wedding ring as a "handcuff." They followed Coco Chanel's lead and cast off the formal (and uncomfortable) bustles, corsets, pantaloons, and petticoats that restricted their movement for the freedom of short, slinky dresses amounting to not much more than a short satiny slip held up by spaghetti straps with maybe some fringe at the bottom. They smoked, drove cars, cropped their hair short, and rebelled against all the gender protocols of earlier eras. Jazz itself was sort of the Hip-Hop of its day. It was all very Punk Rock in its way, and quite badass. Certainly many Speakeasies were high-class establishments requiring black tie and tails and employing less controversial musicians. Perhaps this was more the vibe in the basement of 40 Hilton, but the historical conflict remains, in principle.

The bar room proper is actually incredibly small. No more than about five drinkers could comfortably occupy it at one time. This small room has a door with the requisite peephole on the door, through which the proprietor could see who was requesting admittance and demand the secret password. Outside this is a larger room with the billiard table and a working fireplace. I only asked if it were functional because it seemed strange to me that there would have been a fireplace in the basement at all, until I learned that it originally contained the kitchen. The house has three flues, impressively; this is one. Due to the diminutive size of these two rooms, presumably it was really enjoyed only by personal friends of the hotel's manager and V.I.P. guests at the hotel personally invited to it by him.

Whether or not the owners of the house at the time had connections to organized crime, I'll not speculate, but for sure an illegal bar could never have lasted long without that, an insider connection with the local police department, or at the very least, enough money to bribe constables to look the other way (although there were only two of them). There is still something in the basement that may very well have served as an alarm. In a small nook near the ceiling in a corner of the billiard room, there's this old-timey looking siren. My host said they never quite knew what it was or what it was for. My best guess is that there was a button somewhere on the first floor near the entrance that could set off this siren when the police arrived to bust up the merriment. Oddly, I'd think something as loud as a siren would be heard all through the house, including at the front door, so who knows?

It's incredible enough that there's a Speakeasy there at all, but another piece of the legend makes it all the more fantastic. The rumor was that there was a tunnel dug from the Garden City Hotel two rather long blocks away to the basement of this house so guests could visit the Speakeasy privately. When I visited the house with my friend all those years ago, she showed me this arched cement portal (now containing bookshelves) in the basement that faces the direction of the hotel. At the time, we both agreed this must certainly be the entrance to the infamous tunnel.

On this more recent visit, my host assured me that behind this arch, an alleged tunnel would have had to cut through the extant coal chute, rendering it impossible. He also said that a village historian visiting the house had scoffed at the idea that any such thing ever existed, to his knowledge. With all respect to my host and appreciation for realistic skepticism, I have far too wild and romantic an imagination to ever fully believe there was no tunnel and that that cement arch isn't what remains of it. I'd have gotten a photo of it so you could decide for yourself, but the current family uses their basement for storage as many of us do, and one of my top priorities was to not intrude on their privacy.

Another argument for this story being mere legend is that it would seem an outrageous waste of resources to construct such a tunnel. But Garden City is, and no doubt was then, a conspicuously conservative town. Add to this what is the only four star hotel on Long Island (according to them). Vanderbilts stayed there, Astors, Morgans, Guggenheims, Theodor Roosevelt, John and Jackie Kennedy, Margaret Thatcher, Henry Kissinger, Sarah Ferguson, Hillary Clinton, and Prince Khaled of Saudi Arabia. Perhaps most famously, due to the hotel's close proximity to Roosevelt Field Airport (now a huge shopping mall), Charles Lindberg stayed at this hotel the night before his transatlantic flight in 1927. The point is, these are the type of folks who would not want to be seen strolling down the street from their hotel to what everyone suspects is an illegal drinking hole, especially in a heavily religious community. They'd want to be far more discreet. A suburban residential neighborhood typically doesn't have dark back alleys for slinking into a Speakeasy unnoticed.

The village had a population of only around 2000 at that time, most of them devout Episcopalians forming a congregation for the enormous and majestic Cathedral of the Incarnation (Henry G. Harrison, 1885) a few blocks away. The cathedral and bishop's residence, the schools, and other public buildings were all served by large underground pipes from a centralized heating plant near to the present location of the town's middle school (typically years six, seven, and eight). Oddly, I still remember there being random manhole covers in the school's sports field, but never knew that's what they were. It was also rumored that these pipes were used by boys at St. Paul's to sneak over to visit the girls at St. Mary's, but this was also nothing more than legend. But this may have been what evolved into the legend of the Speakeasy tunnel. Moral of the story, this particular tunnel may never have existed, but I would just really love to believe that it did. Someday perhaps an archeological excavation will reveal the truth.

I'd also much rather believe that Lindberg actually did stop off for a Gin Rickey or two at this Speakeasy than to think he preferred to "get a good night's rest," although it's unlikely the eve of his historic trip was his first or last time at Roosevelt Field or staying at the hotel. He may have been a regular, in fact. My host did tell me that evidently the president of Ford Motors drank at the little basement bar some time in the 1950s, when holding that post was Henry Ford II. I'm not sure what I'm supposed to make of this synchronicity, but there is actually an old photograph showing Henry and Edsel Ford, subject of a relatively recent post here, with Lindberg, who appears in this post.

It is possible that the basement bar remained in use as a modest nightspot into the mid-1930s--although I rather doubt the owners at the time would have wanted anyone other than close friends in their private home once it was no longer a social and legal necessity. Without question, if there ever were a tunnel, it would have been sealed off shortly after Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

|

| Photo courtesy Huffington Post. |

The hotel quite tragically went bankrupt and this incredible structure was demolished in 1973. From 1973 until 1980, it was an unassuming one-room building by an unknown architect. It was then rebuilt and reopened at a larger size again. The interiors, with antiques personally selected in Europe by the owner's daughter, Cathy Nelkin, are appropriately luxurious, but the exterior is entirely forgettable, especially compared to its earlier manifestations. In fact, no one anywhere seems to have any idea of the identity of the architect or architectural firm responsible for its present design.

Sometime before the current owners purchased 40 Hilton in around 1986 or so, an owner of the house had removed the staircase leading from the third floor to the cupola or "widow's watch" on the roof, replacing it with a closet. That term, by the way, comes from the tale that the widow would use a cupola like this to go up and watch for her husband lost at sea returning home again.

The cupolas on the Apostle houses had a tendency to easily rot. As a result, most of them were removed. That along with the refacing of exteriors on some of them and other alterations over the years makes it almost impossible now to see that they were all once identical. Since their cupola was rotting as well, the former owners of this house just sealed up the opening in the ceiling. I suppose I'd like to blame the 1970s for this, a decade relatively unkind to architecture. But in fairness, before the advent of double-glazed windows, the cupola likely sucked all the warm air right up out of the house in the wintertime, even with the door closed.

My host told me that, thankfully, they needed to make very little structural improvements to the house. He said the previous owners had chosen relatively accurately Victorian wallpapers and decor, but that a lot of the colors were rather dark (as Victorian rooms often were). They lived with it for a while before deciding it was time to brighten up the house a bit. He also said they might have gone a bit further in their restoration, but could find absolutely no original floor plans for this house anywhere. One of the more involved restorations they undertook was to open up the cupola again, install a fold-down stair as you'd see accessing an attic, repair the rotted cupola itself, and create a roof deck surrounding it. It was really quite stunning up there--this house is one of the tallest buildings around. I was sort of hoping to see the hotel from the roof, but the hundred-year-old trees in the neighborhood are taller than anything else, including this house.

|

| If there'd been a ghost in this picture, I'd have been SO excited. |

That the strange occurrences seemed to coincide with the opening of the rooftop cupola is a bit odd, because I'd think the characters to be found in the Speakeasy downstairs would have been a lot more colorful than some demure Victorian girl. Speakeasy patrons could use a restroom in the basement, however. My friend had also shown me that in one of the bedroom closets, there's a small, maybe four-foot-high door (a little over a meter high) leading to some kind of secret passageway. Where it led, she'd never known. My host said it merely leads to one of the other bedrooms, but just the idea that there would be a secret passageway in this house is so delightfully perfect.

My friend and I were somewhat Goth at the time (my excuse is that we were seventeen), so the whole experience was a bit like hanging out with Lydia, Winona Ryder's character in Beetlejuice. Granted, my friend was considerably more upbeat and fun than Lydia Deetz, so I mean that in a very, very good way. I think the enthusiasm of this post proves that well enough. The current owner seemed to suggest that there hasn't been too much mysterious toilet flushing for a while, but he told me that when it does happen, it always seems to be right around this time of the year.

While I would be pleased to present this story to you at any time, I'm especially elated that it worked out in such a way that I could post it now, just as we near Halloween 2012. For readers who may live in other parts of the world, Halloween is the festival in the United States celebrating the deceased, although it's sort of evolved into something very different now. As a matter of fact, this story was completed a couple weeks ago. On the recommendation of a good friend to whom I told some of this story, I decided to wait and publish it much closer to the holiday. Not that the house at 40 Hilton is spooky in any way, mind you. In my opinion it's absolutely beautiful. If I were a ghost, I'd probably want to stick around, also.

All text and 40 Hilton photos ©2012, Ryan Witte.

Friday, October 5, 2012

GET LOST: A New York Tour Guide's Guide to New York #12d

12d. TRANSPORTATION--TAXI CABS

It might seem that taxis would be faster than waiting for trains, but this is completely true only at night. During the day, for all the same reasons that most New Yorkers don't own cars, it can actually be a huge waste of time and money. The one thing they do offer is privacy and comfort compared to the trains. Late at night, the one time I might certainly recommend taking a cab, you can get from just about any destination to another in the central part of Manhattan in less than fifteen minutes and for under fifteen dollars including the tip. Often it's much less.

During the daytime, cabs are only worth taking for distances between around fifteen and forty blocks (street blocks, that is, not avenue blocks). Less than that and, considering the cost and slowness, you may as well just walk it. Much more than that and you'd likely get there much faster and for much less money by taking the subway. One exception is if you have luggage or other heavy items on you, especially trips to and from the airport.

There are fifteen different vehicles authorized by the Taxi & Limousine Commission, the most recent of which, the Nissan NV200 shown here, was introduced as the "Taxi of Tomorrow" at this year's auto show. A few of them, namely the Mercedes E350, Volkswagen Golf, and AM General MV-1, I have never once seen on the street. For those who may be environmentally conscious, eight of the fifteen have hybrid models available. The NV200 will soon be available as an electric vehicle, as will the Volkswagen Jetta. The Jetta is also available in a version which burns biofuel. I have every confidence the city chose these particular models for that very reason. The number of hybrid taxis continues to rise, and customers appear to prefer them. Although they certainly produce less pollution as well, resources must also be tapped for maintenance and repair, which produce different kinds of pollutants, and have been so costly as to call into question the benefit of savings on fuel usage. In fact, a plan to replace every New York City taxi in use to hybrid models by a certain year had to be scrapped for this reason.

The next thing to discuss is hailing. I'm always shocked by how often I see people who appear comfortable in the city who don't seem to understand how the fare lights work. They stand there waving their hand in the air becoming increasingly agitated and insulted as taxi after taxi passes by them. There has been discussion about changing the fare lights to make them more intuitive and easier to understand, but until that happens, here it is.

When I say fare lights, I refer to the little light box on the roof right above the windshield, facing front. It has three settings. All the lights off means the cab has a fare on board and is unavailable. The taxi's ID number lit alone means the cab is available to accept a fare. If this cab passes you by, you have right to be insulted unless the driver is unable to merge lanes or some other issue. On both sides of the ID number are two more lights that read "off duty." This is fairly self-explanatory unless you're too far away or didn't think to read what it says. If all the lights are lit, the cab is unavailable. Yes, I know, that's stupid. But that's how it works.

There is a provision on off-duty cabs, however. Since the driver is obviously traveling somewhere, what this usually means is that he or she is changing shifts. Most cabs are shared between two drivers, one taking the day shift, the other taking the night shift. The bizarre thing about the shift change is that it happens when you'd least expect it, between 4:00 and 5:00PM. It has to do with ensuring that both shifts include a rush hour, and avoiding the day shift starting at, say, 2AM. But it means that when you'd most want to have a cab take you somewhere, there aren't any.

In any case, you may occasionally see an off-duty driver stopping for a potential fare, but rolling down the window first to ask where the person needs to go. If the driver is going generally in the same direction as the potential customer, he or she will usually be happy to pick up one last customer before quitting time. Don't be insulted if the driver simply says "sorry, no," and speeds off. This just means your destination is too far out of the way. The taxi stations are mostly out in Queens somewhere and the driver will be fined for getting the car back late.

It's possible that if you have an emergency, you could offer an off-duty driver more money to take you, for instance, double what the meter says. I've never seen anyone try this to know if it would work. Likely more money wouldn't make a difference unless you're willing to cover the driver's potential thirty-dollar late fee.

Typically the most people a single taxi will agree to take is four, unless you get one of the minivan ones with more seats. If you're overflowing the back, some drivers prefer you ask first before taking the front seat. If you have more people than the vehicle is supposed to hold, you'll need to ask the driver if he or she is willing to accommodate you, and it's probably not a bad idea to offer some extra money for he or she taking the risk. Most of the time you'll need to split your group between two cabs.

Once you've gotten into the cab there is one crucial thing you need to have for where you want to go: the street and avenue intersection ("61st & Lex") or mid-block location between two others ("39th between 2nd & 3rd Avenue"). The numbered street address of the specific building is great to have, but unless it's on a major artery, the driver is likely to just guesstimate into what block that building address falls. Certainly smart phones are quickly making this kind of advice obsolete, but I still think it's wise to do your own homework.

I used to know a person with whom it was so embarrassing to take cabs because he would get in and order the driver to take us to "Such-and-Such Obscure Expensive French Restaurant, please," as if the driver should have any clue where that is. Then he would proceed to complain loudly enough for the driver to hear him how New York City cab drivers don't know where anything is. In a way, it was extra rude because we'd be going someplace this unfortunate cab driver probably couldn't even afford to go.

In some cities like London, taxi drivers must pass an extensive exam and know exactly how to get to just about every last random address in the city. Unlike the potentially confusing city of London, likely because of the numbered grid, New York cab drivers don't have to memorize every street to get the job. Whatever you think about that, it's just how it is. Central Manhattan, where most people are going, is easy enough. But the city as a whole is a big place. There are enormous stretches of eastern Brookyn where I have never even set foot, and in a car, would be hopelessly lost in five minutes.

Most drivers know the location of major sites in Manhattan, especially things like train stations and larger cultural venues, because these are the places where they're guaranteed to find fares. But some random little hotel? Forget it. Know where you're going. In the outer boroughs, it can often be necessary to have a vague idea of what route you need to take, as well.

There's another unfortunate reason why it's so important to know exactly where you're going. I'm sorry to have to say this, but the driver will probably try to rip you off. The good news is that there's nothing that can be done to mess with the meter. The meter is automatic, must be used for every ride, and it's calculated pretty well to benefit both the driver and the passenger fairly, regardless of whether you're speeding along fast or stopped in horrible traffic. But I cannot tell you how many times I've been in a cab with someone who the driver only suspects is from out of town and suddenly I find we're going around and around in circles, or taking the, ahem, "scenic route" to our destination.

Usually they won't screw around if you're going to the airport. They know you'll lose your marbles if you think you're going to miss your plane. But if you're headed to a hotel, the driver will probably assume you have no idea where you are and won't notice an extra trip around the block. A lot of the new cabs have a screen in the back which includes GPS mapping of your route, but if you don't know the city geography and aren't watching the screen extremely closely the entire time, this might not help all that much--and give you motion sickness in the process.

A friend who worked in hospitality recently made me aware of a really smart move in this situation: telling the driver he or she missed your turn and asking that the meter please be stopped. Give him or her the benefit of the doubt that it may have been an honest mistake. Insinuating that the person is a crook won't do anything but make the scene needlessly ugly. Remember that a lot of the streets do go only one way, and that the driver may have had no choice but to circle around. Getting out on the nearest corner and walking an extra fifty yards to your destination rather than being taken right up to its front door can help to avoid this question, also. If the driver refuses to turn off the meter and you are certain you were being taken on the long route, don't tip. Making a mental note of the driver's ID number is never a bad idea--it's only four digits, easy to memorize--especially if you later discover your cell phone fell out of your pocket in the cab.

And please do tip otherwise, especially if you got there faster than you thought you would or the driver helped with your lead-bullion-filled luggage. Driving a cab is a thankless job with obnoxious passengers, traffic accidents, nutjobs, and muggers. Cab drivers aren't living in twelve-bedroom mansions as it is. A lot of them are honest folks working their way through college, hardworking parents just trying to feed their kids, or retirees for whom social security isn't enough. Lastly, do not ever assume, just because your driver doesn't speak flawless English and is likely newly immigrated to the United States, that he or she doesn't have two doctorates in neurobiology from the best university back home. Trust me, a lot of them do, but those jobs aren't so easy to find here, at least not immediately upon arriving.

©2012, Ryan Witte

12e. Livery Cabs

It might seem that taxis would be faster than waiting for trains, but this is completely true only at night. During the day, for all the same reasons that most New Yorkers don't own cars, it can actually be a huge waste of time and money. The one thing they do offer is privacy and comfort compared to the trains. Late at night, the one time I might certainly recommend taking a cab, you can get from just about any destination to another in the central part of Manhattan in less than fifteen minutes and for under fifteen dollars including the tip. Often it's much less.

During the daytime, cabs are only worth taking for distances between around fifteen and forty blocks (street blocks, that is, not avenue blocks). Less than that and, considering the cost and slowness, you may as well just walk it. Much more than that and you'd likely get there much faster and for much less money by taking the subway. One exception is if you have luggage or other heavy items on you, especially trips to and from the airport.

There are fifteen different vehicles authorized by the Taxi & Limousine Commission, the most recent of which, the Nissan NV200 shown here, was introduced as the "Taxi of Tomorrow" at this year's auto show. A few of them, namely the Mercedes E350, Volkswagen Golf, and AM General MV-1, I have never once seen on the street. For those who may be environmentally conscious, eight of the fifteen have hybrid models available. The NV200 will soon be available as an electric vehicle, as will the Volkswagen Jetta. The Jetta is also available in a version which burns biofuel. I have every confidence the city chose these particular models for that very reason. The number of hybrid taxis continues to rise, and customers appear to prefer them. Although they certainly produce less pollution as well, resources must also be tapped for maintenance and repair, which produce different kinds of pollutants, and have been so costly as to call into question the benefit of savings on fuel usage. In fact, a plan to replace every New York City taxi in use to hybrid models by a certain year had to be scrapped for this reason.

The next thing to discuss is hailing. I'm always shocked by how often I see people who appear comfortable in the city who don't seem to understand how the fare lights work. They stand there waving their hand in the air becoming increasingly agitated and insulted as taxi after taxi passes by them. There has been discussion about changing the fare lights to make them more intuitive and easier to understand, but until that happens, here it is.

When I say fare lights, I refer to the little light box on the roof right above the windshield, facing front. It has three settings. All the lights off means the cab has a fare on board and is unavailable. The taxi's ID number lit alone means the cab is available to accept a fare. If this cab passes you by, you have right to be insulted unless the driver is unable to merge lanes or some other issue. On both sides of the ID number are two more lights that read "off duty." This is fairly self-explanatory unless you're too far away or didn't think to read what it says. If all the lights are lit, the cab is unavailable. Yes, I know, that's stupid. But that's how it works.

There is a provision on off-duty cabs, however. Since the driver is obviously traveling somewhere, what this usually means is that he or she is changing shifts. Most cabs are shared between two drivers, one taking the day shift, the other taking the night shift. The bizarre thing about the shift change is that it happens when you'd least expect it, between 4:00 and 5:00PM. It has to do with ensuring that both shifts include a rush hour, and avoiding the day shift starting at, say, 2AM. But it means that when you'd most want to have a cab take you somewhere, there aren't any.

In any case, you may occasionally see an off-duty driver stopping for a potential fare, but rolling down the window first to ask where the person needs to go. If the driver is going generally in the same direction as the potential customer, he or she will usually be happy to pick up one last customer before quitting time. Don't be insulted if the driver simply says "sorry, no," and speeds off. This just means your destination is too far out of the way. The taxi stations are mostly out in Queens somewhere and the driver will be fined for getting the car back late.

It's possible that if you have an emergency, you could offer an off-duty driver more money to take you, for instance, double what the meter says. I've never seen anyone try this to know if it would work. Likely more money wouldn't make a difference unless you're willing to cover the driver's potential thirty-dollar late fee.

Typically the most people a single taxi will agree to take is four, unless you get one of the minivan ones with more seats. If you're overflowing the back, some drivers prefer you ask first before taking the front seat. If you have more people than the vehicle is supposed to hold, you'll need to ask the driver if he or she is willing to accommodate you, and it's probably not a bad idea to offer some extra money for he or she taking the risk. Most of the time you'll need to split your group between two cabs.

Once you've gotten into the cab there is one crucial thing you need to have for where you want to go: the street and avenue intersection ("61st & Lex") or mid-block location between two others ("39th between 2nd & 3rd Avenue"). The numbered street address of the specific building is great to have, but unless it's on a major artery, the driver is likely to just guesstimate into what block that building address falls. Certainly smart phones are quickly making this kind of advice obsolete, but I still think it's wise to do your own homework.

I used to know a person with whom it was so embarrassing to take cabs because he would get in and order the driver to take us to "Such-and-Such Obscure Expensive French Restaurant, please," as if the driver should have any clue where that is. Then he would proceed to complain loudly enough for the driver to hear him how New York City cab drivers don't know where anything is. In a way, it was extra rude because we'd be going someplace this unfortunate cab driver probably couldn't even afford to go.

In some cities like London, taxi drivers must pass an extensive exam and know exactly how to get to just about every last random address in the city. Unlike the potentially confusing city of London, likely because of the numbered grid, New York cab drivers don't have to memorize every street to get the job. Whatever you think about that, it's just how it is. Central Manhattan, where most people are going, is easy enough. But the city as a whole is a big place. There are enormous stretches of eastern Brookyn where I have never even set foot, and in a car, would be hopelessly lost in five minutes.

Most drivers know the location of major sites in Manhattan, especially things like train stations and larger cultural venues, because these are the places where they're guaranteed to find fares. But some random little hotel? Forget it. Know where you're going. In the outer boroughs, it can often be necessary to have a vague idea of what route you need to take, as well.

There's another unfortunate reason why it's so important to know exactly where you're going. I'm sorry to have to say this, but the driver will probably try to rip you off. The good news is that there's nothing that can be done to mess with the meter. The meter is automatic, must be used for every ride, and it's calculated pretty well to benefit both the driver and the passenger fairly, regardless of whether you're speeding along fast or stopped in horrible traffic. But I cannot tell you how many times I've been in a cab with someone who the driver only suspects is from out of town and suddenly I find we're going around and around in circles, or taking the, ahem, "scenic route" to our destination.

Usually they won't screw around if you're going to the airport. They know you'll lose your marbles if you think you're going to miss your plane. But if you're headed to a hotel, the driver will probably assume you have no idea where you are and won't notice an extra trip around the block. A lot of the new cabs have a screen in the back which includes GPS mapping of your route, but if you don't know the city geography and aren't watching the screen extremely closely the entire time, this might not help all that much--and give you motion sickness in the process.

A friend who worked in hospitality recently made me aware of a really smart move in this situation: telling the driver he or she missed your turn and asking that the meter please be stopped. Give him or her the benefit of the doubt that it may have been an honest mistake. Insinuating that the person is a crook won't do anything but make the scene needlessly ugly. Remember that a lot of the streets do go only one way, and that the driver may have had no choice but to circle around. Getting out on the nearest corner and walking an extra fifty yards to your destination rather than being taken right up to its front door can help to avoid this question, also. If the driver refuses to turn off the meter and you are certain you were being taken on the long route, don't tip. Making a mental note of the driver's ID number is never a bad idea--it's only four digits, easy to memorize--especially if you later discover your cell phone fell out of your pocket in the cab.

And please do tip otherwise, especially if you got there faster than you thought you would or the driver helped with your lead-bullion-filled luggage. Driving a cab is a thankless job with obnoxious passengers, traffic accidents, nutjobs, and muggers. Cab drivers aren't living in twelve-bedroom mansions as it is. A lot of them are honest folks working their way through college, hardworking parents just trying to feed their kids, or retirees for whom social security isn't enough. Lastly, do not ever assume, just because your driver doesn't speak flawless English and is likely newly immigrated to the United States, that he or she doesn't have two doctorates in neurobiology from the best university back home. Trust me, a lot of them do, but those jobs aren't so easy to find here, at least not immediately upon arriving.

©2012, Ryan Witte

12e. Livery Cabs

Labels:

automobiles,

Get Lost,

New York City,

tourism,

transportation,

travel

Sunday, September 2, 2012

Prodigal Roadster

|

| Photo courtesy RM Auctions. |

|

| Photo courtesy Oregon CCCA. |

The Lincoln Model K was introduced in 1931. In 1932 it was split into two lines, the KA and the KB. The 1932 Lincoln Model KA V8 Victoria shown here was clearly fancier, more powerful, and more luxuriously detailed than a Ford. It sold for a little over $4400 in '32, almost $70,000 by today's standards. Despite the outrageous price difference, it's not all that significantly different in style.

In 1932, Edsel Ford went on a trip to Europe. Who knows if his primary goal was to get a look at the European cars, but there probably can be not the slightest question that someone as intimately involved with the automobile industry would have his eye on every new car he saw. What's more, if a man like Edsel Ford were visiting Europe, I can't imagine he wasn't eating most of his dinners at the homes of people like Aston Martin founder Lionel Martin and Bindo Maserati. I don't know exactly where he went or what he saw there, but I'd like to try to piece it back together using some possibilities.

|

| Photo courtesy Steve Sexton. |

I can't be convinced that Ford went to Germany at all. Porsche was only a consulting firm at the time, anyway. There is some possibility that he saw the BMW Wartburg DA3, but it was kind of such a frumpy little thing that I can't imagine he would have been very impressed by it, not to mention that it almost looks taller than it does long. I also find it hard to believe that he could have seen the Mercedes-Benz SSK Trossi (named for its first owner, racecar driver Count Carlo Felice Trossi). First of all, very few of them were ever made, so it's not as if he were likely to have stumbled onto one on the road or even in a showroom. Plus, its design by Ferninand Porsche would have been so shockingly futuristic and--if I had to guess--astonishingly beautiful to Ford that its influence would have been far more apparent in what he ultimately created. I mean, for crying out loud, the thing looks like a freaking Batmobile. Although it does have the tapered tail, that could be found on plenty of race cars at the time. Mercedes' regular-production cars tended to be high and regal like the Rollses and Bentleys...and the concurrent Lincolns.

Traveling through France, there wasn't much to see. The Renaults and Citroëns were higher and boxier than the Fords, and neither Citroën nor Peugeot would introduce streamlined models until well into 1933 or 1934. There's really no way he couldn't have noticed the gorgeous Bugatti Type 50T, but I suspect it was a bit too voluptuous for him and not exactly what he was looking for. Avions Voisin, although decidedly interesting and even distinctive, rested somewhere between clunky and relatively bizarre.

|

| Photo courtesy David van Mill. |

|

| Public domain. |

Perhaps it should come as no surprise that the car that appears to have impressed Ford the most was a Maserati. It was the 8C 3000, designed by the eldest Maserati brother, Alfieri, who passed away before he could see it finished. It has the correctly raked front end (a tiny hint of the streamlining to come) and the tapered rear end, in addition to the comparatively low profile of all the others.

|

| Photo courtesy Gerry Swetsky. |

When Ford returned home, he began talking to his company's head designer, E. T. "Bob" Gregorie, asking him to design a new car based on what he'd seen and liked in Europe. The first design was actually taller than Ford wanted, so Gregorie went back to the drawing board and finally created something much more streamlined. The normal Ford roadster chassis was modified and lowered by slinging it under the axle.

The tail extends further out in the back, making it appear longer and lower than a typical Ford. The new car was built by the Ford Aircraft Division using the same tubular aluminum construction methods, making the body extremely lightweight and strong. Along with its exhaust pipes, its headlights and taillights were sunk into the body itself, an innovation of Ford's for which I could find no European precedent, but which clearly made the overall design more streamlined still.

The final result of all of this was Edsel Ford's 1934 Model 40 Special Speedster.

|

| Restoration and vintage photos courtesy Ford Hous |